The Ballista

The ancient Greek Ballista first appears in historic literature in the 4th century b.c. and made very creative use of the newly invented Torsion Spring. (See siege engine mechanics for details.) The design of the ballista was such that it could be built in small to large sizes and could be configured to throw either stones or bolts.

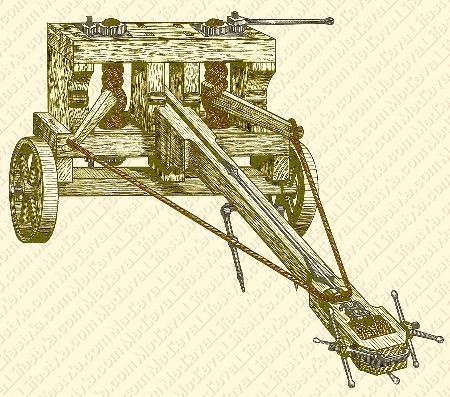

Eventually becoming primarily a bolt thrower, the ballista was used by attackers and defenders alike as an effective anti-personnel weapon. For defenders, the positioning of ballistas (ballistae) upon the walls of a fortification would afford additional range to the weapon, and some versions were built on a pivoting frame to allow for quickly repositioning a shot. For attackers, another version of the ballista was wagon mounted, the carro-ballista, allowing it great mobility in the field. The ballista could also be a powerful delivery system for the launching of flaming bolts over distant walls.

Mechanism of the Ballista

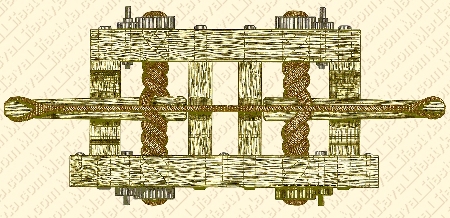

Although the ballista looked somewhat like a large frame-mounted crossbow, its mechanism of propulsion was quite different. Two torsion springs mounted in a frame and wound in opposite directions each retracted a resilient throwing arm. A rope, analogous to a bow string, connected the two throwing arms, and this rope was mechanically retracted into firing position.

The throwing arms of the ballista were originally engineered using fused lengths of wood and animal sinew (tendon tissue), the whole then wrapped in animal hide. The result was a strong but light-weight, resilient arm capable of a "fast snap." Over the ensuing centuries the Romans absorbed and transmuted the original Greek designs for this and other weapons. Eventually the manufacturing subtleties were lost, leaving present-day researchers to ponder how exactly the early engines were constructed.

The only weakness of the ballista was inherent in the torsion spring itself. When new properly crafted springs were used during the daytime in mild weather, the weapon worked as designed; however, rainy weather, humid air, or even the morning dew could negatively affect the performance of the springs. Over time the cordage would slacken, and under some circumstances it might be difficult to stockpile the necessary materials for repair.

A Bolt of Intimidation

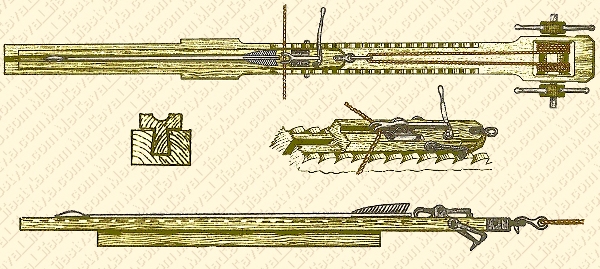

A large ballista could launch an imposing javelin weighing up to 10 pounds. The steel bolt might be four to six feet long with a shaft two-and-a-half inches in diameter. The "feathering" consisted of about eight inches worth of wood, horn, or brass laminates. Affixed to this intimidating rod was a steel head weighing three to five pounds.

The bolt would be loaded into a sliding trough in the stock of the ballista. The trough was then cinched back into firing position by the windlass. (See Siege Engine Mechanics.) This sliding holder was dovetailed into the stock and was fashioned in such as way so as to be retained upon firing.

See Medieval Castles for more information on castle sieges.

For information on other siege engines see our main Siege Engines page.