Siege Engine Mechanics: Sticks & Stones

The propulsive forces behind medieval siege weaponry were torsion, traction, and tension. These forces are generated as follows:

The Three T's of Siege Engine Mechanics

Torsion — Twisting

Torsion is a the force created when a twisted object seeks to unwind. Two of the "big three" engines of war described in these pages are torsion-propelled machines. The catapult utilized a single torsion spring (detailed below), and the ballista made use of two such springs.

Traction — Pulling or Dragging

The pulling or dragging of an object applies the force of traction. Two examples of siege machines employing traction are the perrier and the trebuchet. Both were lever-type machines where one end of the lever would be pulled, and the other end flung a missile. The perrier was propelled by simple manpower; whereas, gravity did the pulling for the trebuchet.

Tension — Bending or Stretching

Similar to the concept behind torsion, tension occurs when a material which is bent or stretched seeks to return to its normal state. One example of a siege machine utilizing this force would be the giant arbalest, essentially a massive frame-mounted crossbow that could shoot bolts or stones. The power to launch the missile came from the tension and compression of the resilent materials of the bow. Another engine utilizing tension would be the springald, a large flexible upright beam cinched back then released. Siege weapons powered by tension were also referred to as spring engines.

The Torsion Spring

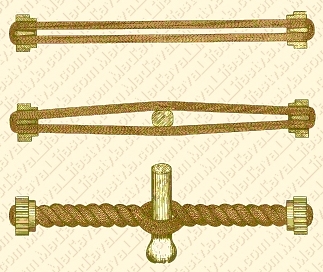

One of the most important milestones in the evolution of siege engine mechanics was the invention of torsion springs. The illustration details how the spring is constructed.

Cordage for the torsion spring would preferably be made from either horse hair or animal sinew (tendon tissue) from the necks of oxen or horses. Under tension the cordage was looped lengthwise into a large skein held taut on a frame. The shaft of the throwing arm was then inserted into the skein, and the gears of the holding mechanism were turned on both ends to twist the spring tight.

The springs would grow slack with repeated use and periodically had to be replaced. It has been noted that in an emergency situations where horse hair was unavailable, women donated their long tresses for spring construction.

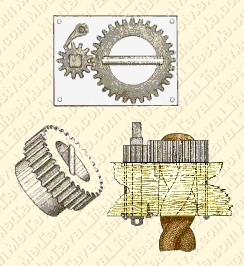

Ratchet & Pawl

To twist the skeins of the torsion spring the method of choice eventually became the ratchet and pawl. Simply put, the ratchet is a toothed gear. The pawl is a little lever which glides over the teeth of the ratchet when the ratchet is turned in one direction only. If the ratchet begins to turn in the opposite direction, the pawl jams the wheel to a stop. This mechanism allows great tension to be developed in the spring.

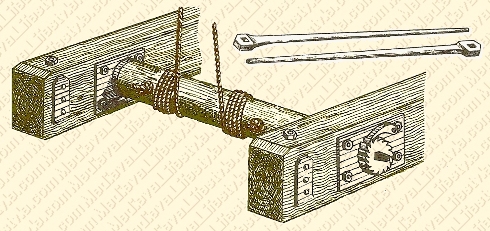

The Windlass

The ratchet and pawl mechanism was also an important part of the windlass, a device used to crank down the throwing arm(s). A windlass is simply a mechanical winch, a drum upon which is turned a length of rope or chain.

The simplest example of a windlass would be a roller with a handle used to crank up the water bucket from an old-fashioned well.

The throwing arms of catapults or ballistas would be put under tremendous tension by the torsion springs. Therefore a sturdy mechanism such as the windlass was necessary to pull the arms into firing position.

In the catapult the windlass was built into the frame, and its rope pulled back the single arm. In the ballista a smaller windlass was built into the stock, and its rope would pull back another rope attached between the two throwing arms, much like one would draw back a bowstring.